Strong Southwestern Sisters

Laura Kuykendall, SU’s first dean of Women and one of SU’s first female drivers; photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Ever stroll through the Southwestern University campus? Go ahead—”townies” are welcome to enjoy the beautiful old and new buildings and reflect on a history of Georgetown support for its highly rated hometown university.

The 16th and first female, SU President Laura Skandera Trombley

And for those who appreciate that women are ever gaining an equitable position in our culture, enjoy the fact that Southwestern University now has its first female president! Learn more about awesome President Laura Skandera Trombley here. She’s a seasoned leader and Mark Twain expert and writes about equity in academia and much more.

The McCombs Center

A good place to start a campus walkabout is the “Commons”: the Red and Charline McCombs Campus Center. SU has thrived with the generosity of many wonderful donors, including untold smaller donations from SU fans. We thank them all! As you wander the campus, you’ll see women’s names along with men’s among the named buildings. Consider the reality that women are often key decision-makers for the financial gifts that make communities better through funding schools and hospitals and libraries and other fundamental community assets.

So, here’s a bit about Charline Hamblin McCombs. She met Red while they were standing in line to enroll in courses at Del Mar Junior College. She graduated from SU, surely unaware that someday SU would host the Charline Hamblin McCombs Residential Center. As Red grew an automative fortune from a start as a greenhorn car salesman, she was an active adviser as the family empire grew, in addition to running a household and raising daughters.

Charline often directed their donations toward women: Her funding of the UT softball field named after her and Red was the biggest gift ever to women’s athletics. She gave generously to causes ranging from arts education for low-income children to better cancer care for all. Thanks, Charline!

Gloria Anzaldua

The McCombs Center has hosted many amazing female speakers, including those who came for student-led events. For example, Latina students including Iliana Sosa put together a 2005 conference that brought scholar and poet Gloria Anzaldua, writer Sandra Cisneros, and other luminaries such as author Carlos Fuentes.

Iliana Sosa

These students presented the first ever Latina/o conference at SU! Iliana, by the way, is a filmmaker now, making films about the US border and family and politics.

Head on over to the lovely Lois Perkins Chapel, and “meet” its namesake.

Lois Perkins Chapel

Lois Craddock came to Southwestern in 1908 from tiny China Springs, Texas, near Waco. She had some tough going growing up: Her mother died early, and she took on the task of raising her siblings.

Lois Craddock Perkins

She studied at Southwestern for three years; illness kept her from getting a degree. Nonetheless, she taught school in Wichita Falls with the hope, she wrote, of giving back some of what she got from her beloved SU days.

She also married wealthy businessman Joe Perkins, and together they gave much money to Methodist schools such as Southwestern—including funding the Lois Perkins Aid Fund for Young Women at Southwestern. The pair donated a total of $12 million toward the School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas; the school was then named the Perkins School of Theology.

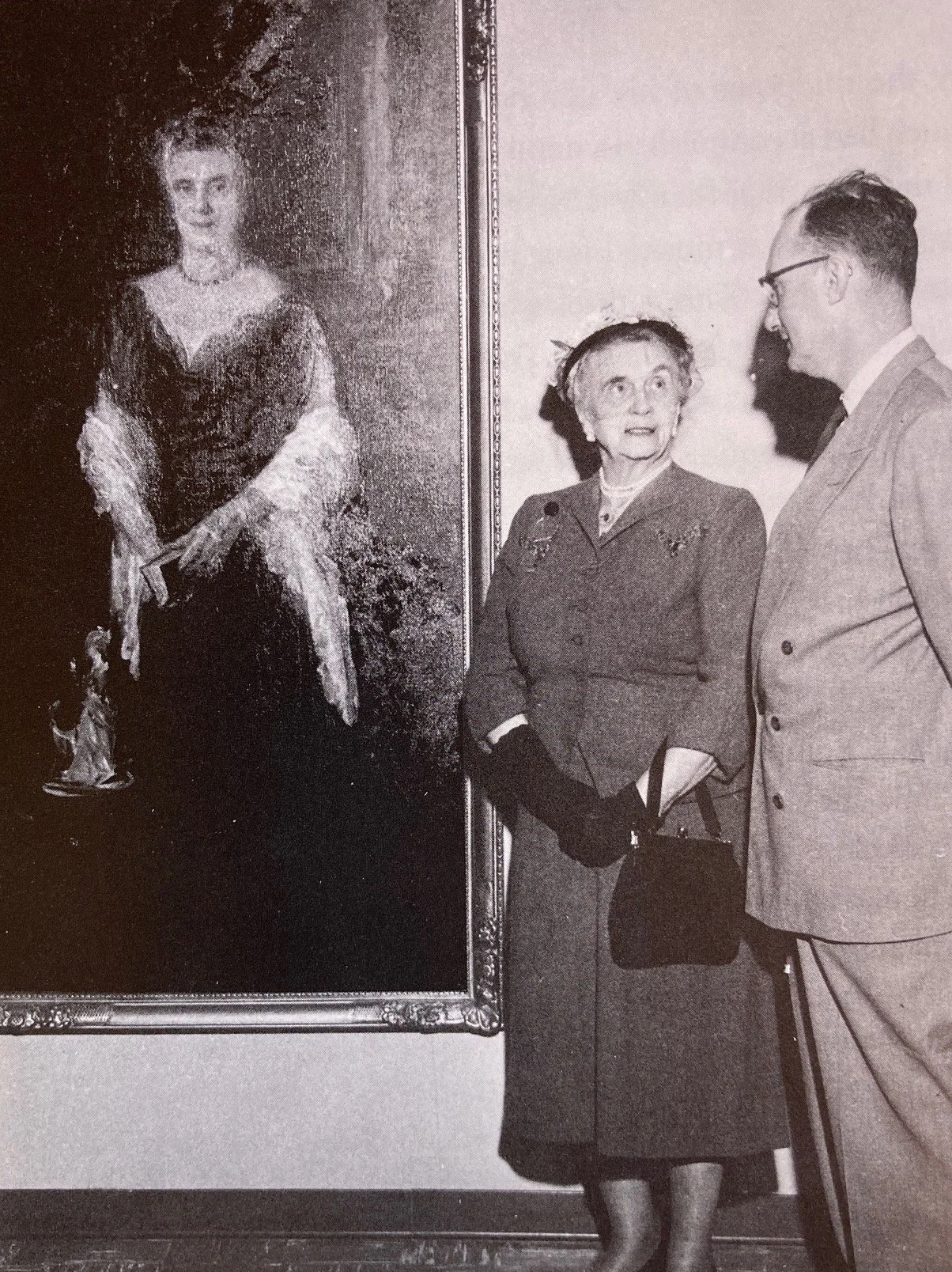

Lois and Joe Perkins look at a drawing of the chapel they funded. Photo from the 1944 Southwestern University yearbook, The Sou’wester

But when Joe was informed in 1952 that five Black students were attending the Perkins theology school, he was not happy. The time was not yet right for integration, he said, instructing the Dean (who was in favor of integration) to “get rid of the Negroes as soon as possible.” When the matter came up later, Lois told the Dean that “I don’t agree with my husband on this matter.”

Perkins Black pioneers graduating in 1955: (L-R) James Arthur Hawkins, John Wesley Elliott, Negail Rudolph Riley, Allen Cecil Williams, and James Vernon Lyles

The Black students stayed and graduated, and much credit is due to Lois. And The Perkins School became the site of the first voluntary desegregation of a major educational institution in the South.

Lois continued to quietly but firmly push for integration at the theology school. When the following dean nervously allowed interracial roommates (something students wanted), he feared more backlash from donors and parents. But Lois made it clear that’s what needed to happen.

As Kevin M. Watson writes in his article on the desegregation of the Perkins school, Lois said, “Now isn’t that grand? We’ve taken another step, and this is something we can be grateful for. Perkins is known around the world as a progressive school . . . Besides, what would I tell my Women’s Society in Wichita Falls if we went back on this advance?”

Lois’s actions exemplify, Watson writes, the important role of Methodist women in advancing racial equality and other causes. This trait of women’s activism is also true for other denominations and faiths.

For example, church women were the core of Georgetown shero Jessie Daniel Ames’ anti-lynching organization. These religious women made it clear to their communities across the South that lynching and racial violence had no place in Christianity.

The ladies make a point.

Another interesting note from the Perkins past: Women were admitted before Black students were, but females in the early years say they felt ignored and not as valued as male students. When the admitted Perkins students of 1969 gathered for a photo, the instructions sent to all the students told them to wear coat and tie. The ladies, making the point that they were graduate students as well, all wore coat and ties!

The Racial History of Southwestern

Southwestern, like Georgetown and other places in the South and US, has a history of racism and segregation. Like most US universities built before or during the Civil War, the colleges that merged to form Southwestern used the work of enslaved people to build and embraced the Confederacy. Many of the prominent families who supported SU also supported the Confederacy and some owned enslaved people.

Learn much more in this excellent website of the Southwestern University Racial History Project. Faculty members and students unfold the racial journey of the four Texas colleges that coalesced to form Southwestern along with SU’s racial journey, and call for continuing work to make SU welcoming to all.

Check out the Placing Memory website. a student-written collection of stories about SU spots and histories, including the racial practices of the four root schools. Students call for a more visible profile of SU’s racial history.

Look to the east side of the chapel in the courtyard for this sculpture, called Madonna and Child.

Margarett had this made for her mother.

Margarett Root donated this sculpture by noted Austin sculptor Charles Umlauff in the memory of her mother, South Carolina Easley Root.

Margarett was a pistol. Raised on a farm outside Georgetown, she pursued arts and literature at Southwestern and was involved in many campus doings and excursions.

After graduation, she taught school in Belton and in 1917, she met Herman Brown, who’d started a road paving business, at a Georgetown dance. Margarett and Herman eloped a few months later, but for their wedding, reports the Texas State Historical Association, Margarett “would not accept a wedding ring because she thought of it as a sign of bondage.” The couple spent their honeymoon in one of Herman’s road construction tents.

Margarett Root Brown

Margarett’s brother, Dan, who had become a prosperous cotton farmer, invested in Herman’s business that was called Brown and Root. Margarett was a Brown and Root partner as it grew into the firm still prominent today as a worldwide industrial services company constructing everything from ships to oilfield equipment.

She also kept up the cultural pursuits she’d loved at SU, participating in the local Woman’s Club and in the Bronté Club, the state’s oldest women’s literary society. The Bronté Club started in Victoria, Texas, in 1855; members founded and grew the Victoria city library.

Margarett was a founder of the Brown Foundation, which has given $1.7 billion in grants to educational, cultural, and civic projects. The Brown Foundation funded the Brown-Cody Residence Hall, which was built in honor of three women whose donations funded endowments and facilities and landscape features throughout the SU campus. Margarett (class of 1915) is one of the three honored, along with Alice Pratt Brown (class of 1924; Alice was a major funder of the Houston Museum of Fine Arts and a close buddy of Lady Bird Johnson) and Florence Root Cody, (class of 1907).

Pearl’s Military Maneuver

Pearl Alma Neas

As you continue your campus saunter, look out on the beautiful Academic Mall and visualize some 400 uniformed men suddenly appearing , eager to learn how to be military officers. That’s what happened starting in 1944, and here’s a key figure to thank. Pearl Alma Neas was skilled at something women can often do: Connect people and unite them to get goals accomplished.

Pearl started out at SU as the President’s secretary in 1913 and worked her way up to being SU’s first-ever female registrar in 1923. She was deeply involved in all things SU, all things Georgetown and Williamson, and all things Democratic Party.

Pearl also built a strong friendship and working relationship with Lyndon Johnson and Lady Bird. She acted as an unpaid political consultant to LBJ, reports William B. Jones in his SU history. LBJ returned her esteem, noting that “I know of no woman whose judgment I admire more.”

Navy men march in front of the Cullen administration building, 1945; photo from the 1945 Southwestern University yearbook, The Sou’wester

Military V-12 grad Kenneth Matthews earned a Purple Heart in the Okinawa battle after training at SU.

SU was facing financial disaster during the WWII years because many male students were now serving in the military and families wary of wartime financial insecurity were reluctant to send their kids to college. Neas worked her connections with Johnson and others to score a V-12 Military Training Unit for the University during World War II. Nearly 400 soldiers came to SU, and the contract saved the SU financial day.

Dorothy went on from V-12 to get six degrees!

By the way, while the great majority of soldiers were men, there was at least one woman, and she was part of the program administration. Dorothy Imogene Popejoy was a Yeoman 3/c, and her assignment at SU was sparked by her patriotic passion after working at a Dallas diesel engine plant supplying the war effort.

After helping run the V-12 program, Dorothy served in three other spots for the Navy. After that, she got three degrees in physical education, teaching and chairing the Women’s Physical Education Department at Michigan State University. After “retiring,” she got three more degrees, including her last at age 84 in Digital Media and Design. She spent her last years doing cat rescue in Arkansas and died in 2022 at age 100.

Nationwide, the V-12 program enrolled 125,000 soldiers at 131 colleges to supplement needed skilled officer needs, and also to prop up colleges decimated by student-age men and women serving in the war or in war-related industry. Pearl’s crucial dealmaking was a lifesaver that kept SU from a tailspin that could have meant closure.

Women’s HQ

After you pass Prothro, take a left to go to the Brown-Cody residence hall. This is the spot where women students spent much of SU’s early history. Because when women were allowed into Southwestern in 1878, they jumped on it bigtime. By 1883—just five years later—women were nearly a third of the students! There were 127 women at SU along with 344 men.

SU women students pour from their dorm then on this spot.

Of course, women could NOT take classes alongside men—who knows what could happen then?? SU administrators promised parents and funders that while women could take classes and get degrees (although only two-year degrees at first), they would not be subjected to what many feared as too radical: “Coeducation.”

So at first, Southwestern women took classes in the basement of the First Presbyterian church at 7th and Church. Then they got a two-story classroom building that was at the intersection of Austin and University—still four chaste blocks away from the men. The all-male SU building at that point was at University and Ash, where the Hammerlun Center is now. Which was the old Georgetown High School.

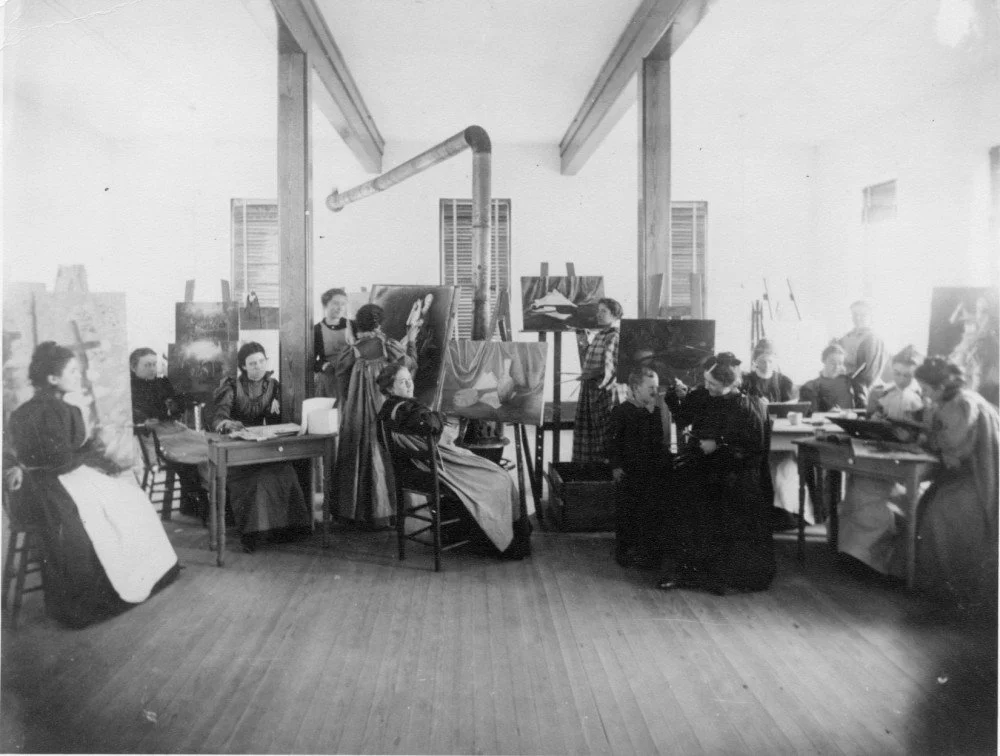

The women outgrew their space, so SU then built the Ladies Annex here in 1887 on what became the SU campus. Women lived and took classes as well in the Annex. Check out the women’s PE class.

Ladies Annex women did everything segregated from men—certainly this gym class! Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Art studio and everything else for classes was all inside the Ladies Annex. Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Fraternization with male students was severely curtailed. And punished! Here are a few rules from many rules forbidding any unauthorized moments with a man.

NO letters! No clandestine communication! Students sometimes succumbed anyway. For example, during the month of April, 1883, 12 young women got demerits for contact with male students. Some were guilty of corresponding with boys; others for conversing (at chapel, even!) with young men; others for walking and appearing in public with them. However, only two young men got demerits that month. Is this sounding familiar? Sounds like the women got punished for “wicked” behavior; most of the men got a pass for participating in same. Takes two to tango, right?

Debates over co-education increased, and students began speaking out for gender desegregation. Men wanted in on some of the women’s classes, and women wanted a full range of classes. It only took 25 years after women started at SU, but by 1903, classes were fully coeducational.

Women students gather before the burned Ladies Annex building they escaped.

Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Sadly, the Ladies Annex burned down in 1925. This woman, SU Dean of Women Laura Kuykendall, was lauded for her calm in getting all the young women out of the burning building.

That was yet another reason that Laura became one of the most loved figures at SU during her stay here from 1914 to 1953. The female (and male) students adored her. Laura knew how to throw some dang fine parties. AND she was a feminist who encouraged women students to pursue whatever they wanted, not what the culture told them they should do.

Both students and townspeople loved Laura’s creativity. She dreamed up gala parties that brought town and gown together. The two-day May Fete featured student royalty, May basket hanging, pageants, and ball games. Her Christmas Carol Candlelight Service was an enchanting evening lit by candles and full of singing, music, readings, and a sit-down dinner. (The candlelit carol event is still an SU holiday tradition.)

And Laura was happy to nurture fun gambits by students, such as this “Talking Club”. Whaddayaknow, these women favorited Men Who Listen!

Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

When Laura came, she was hired in the Department of Expressions. Here she is expressing.

Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Most importantly, Laura emphasized to her female students that they were capable of anything, and she encouraged them to undertake practical and nontraditional learning beyond the expected music and literature and domestic science. As Laura counseled, women used to have the choice of either marriage or spinsterhood, but today females have “the choice of a profession as a third way out.”

Laura gets her Master’s degree.

And Laura modeled accomplishment for the women students as well. While she was Dean of Women, she completed a Masters degree in Sociology and Economics to become SU’s first female Masters grad. Plus she was the first licensed female driver on campus!

Laura DID get into some hot water for tolerating some swearing and cigarette smoking and dancing by female students, and she did some of that herself. She had a more relaxed attitude about male visitors to the dorm’s drawing room.

Laura died suddenly of a stroke in 1935, and her funeral at Southwestern’s chapel was standing room only. In 1941, the Women’s Building was named Laura Kuykendall Hall.

“LK” women’s dorm honors Laura.

In need of renovations, Kuykendall Hall was torn down in 1996. A Laura Kuykendall Garden was created on campus to honor her.

Southwestern women were lucky to get another inspiring Dean of Women. After Laura Kuykendall died suddenly, Mary Ann “May” Catt Granbery was named supervisor of women. She had pursued education at Wesleyan Institute, Mary Baldwin College, and the University of Chicago. She worked for the Y.W.C.A. in war-torn France and Greece.

May was a lifelong feminist and was the editor of The New Citizen, the publication of the Texas League of Women Voters. May and her husband John Granbery (also a staunch feminist and suffrage advocate) were good friends of Jessie Daniel Ames, the Georgetown suffragist and racial justice advocate..

Jessie (on right) and friend on the SU campus

Jessie was perhaps the Ladies’ Annex’s most famous graduate. She graduated with honors in 1902—at age 19. She went on to lead the women of Wilco in the battle for suffrage, with victory in 1918. She and a pack of voter advocates rallied 3,800 women for a voter registration deadline that gave them only 17 days!

Jessie worked hard to educate women about voting and about gaining political power, and became the first Texas president of the League of Women Voters. Then she began work on racial justice: She could see that women of color were not given the same voting and other rights white women had. She then moved to Atlanta in 1930 and started an anti-lynching group called the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. She galvanized thousands of women in the South to get community linchpins such as the police, sheriff, and business leaders to stop lynching before it happened.

Modern suffragists at Jessie’s house and marker

Make sure to stop by her house at 10th and Church and read the big historical marker about her there!

Ernest Clark and SU integration

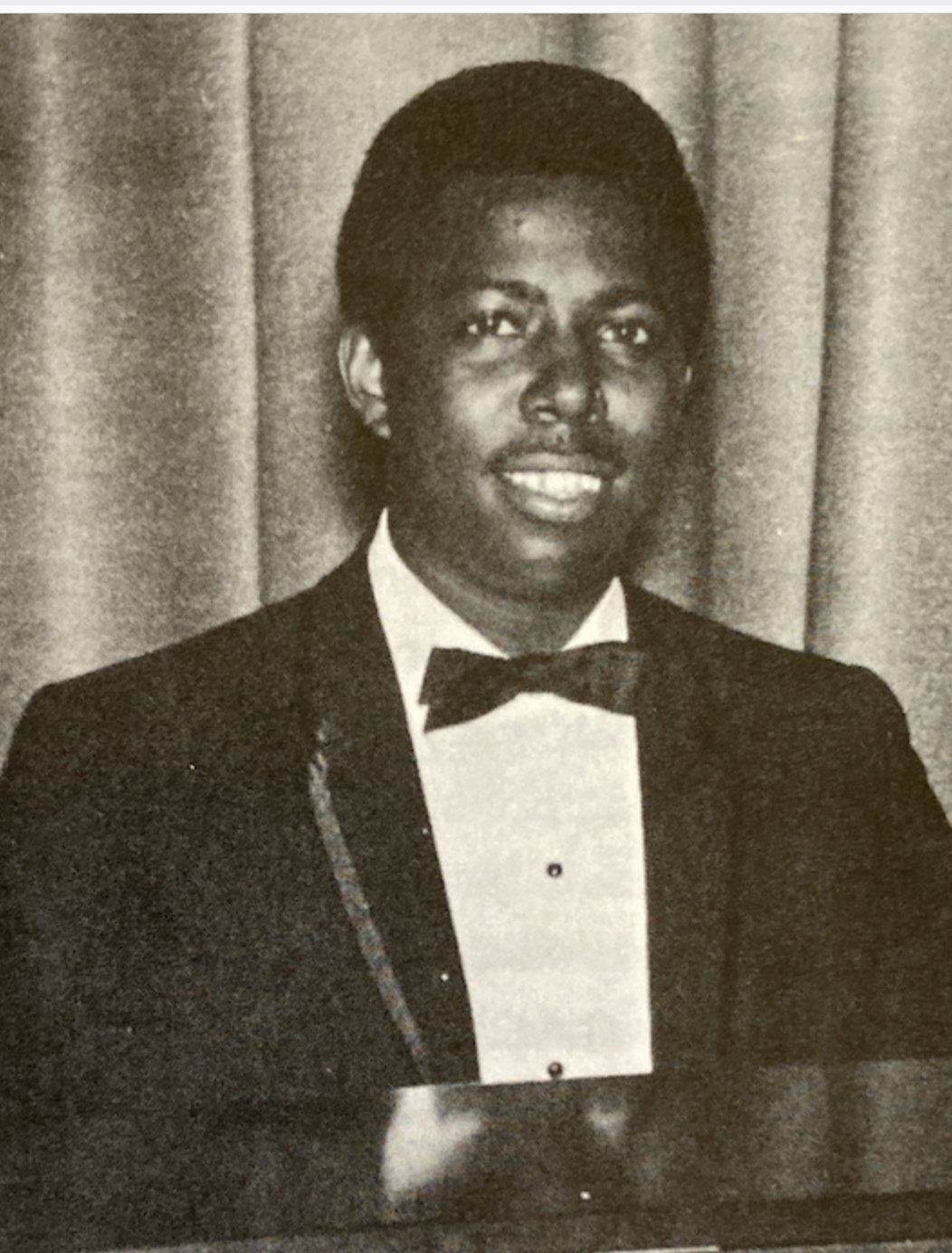

Piano prodigy Ernest at SU

Turn right to see the Ernest Clark Hall. The dorm was renamed to honor SU’s first Black graduate! Ernest came in 1965 and after graduating went on to educate some 36,000 music students in his career. We’ll learn more in a bit about Ernest and the arts program that inspired his love of music. The renaming was from that of SU benefactor Ernest Kurth, who had opposed allowing Black students into SU.

SU quietly began integrating in the later 1960s—thanks to Ms. Freddie Gaines, a school counselor at a segregated Houston high school. She was determined to send more of her grads to white institutions that were integrating. In 1967, her students Alvin Hebert and Winston Phelps enrolled, followed the next year by Lydia Gardner and Gail Rivers. They arrived in pairs so that they could room with each other and not cause any discomfort for white students who wouldn’t want to room with them.

Sammie arrives in 1969.

Freddie’s student Sammie Robinson arrived in 1969, expecting to room with her friend, also sent by Freddie. But before she arrived, Dean of Women Martha Mitten and Dean of Students Bill Swift had quietly asked white students if they would room with a Black student. A few agreed, so Sammie got assigned with two white roommates right here in LK.

Sammie loved her classes, but found social life somewhat challenging. Greek life then as now is a big social hub, and she knew Blacks didn’t get invited to join frats and sororities. On the urging of Dean Mitten, she rushed, but was turned down. She was told that the students would have accepted her, but “our alums would have a fit.”

Sammie is Homecoming Queen, 1972

Sammie and other Black students formed an organization, BOSS—Black Organization for Social Survival. They found an unused room in the top floor of the Mood building and called it the Black Room. They brought in a donated couch and stereo, and created a spot where they could hang out and support each other. The group eventually became the Black Student Union.

Sammie also joined many other student groups and was a resident assistant. She was well-loved and to her surprise, was voted homecoming queen in 1972!

Sammie went on to get a PhD in management, taught college, mentored other Black women, and still consults as an executive coach.

Library Ladies

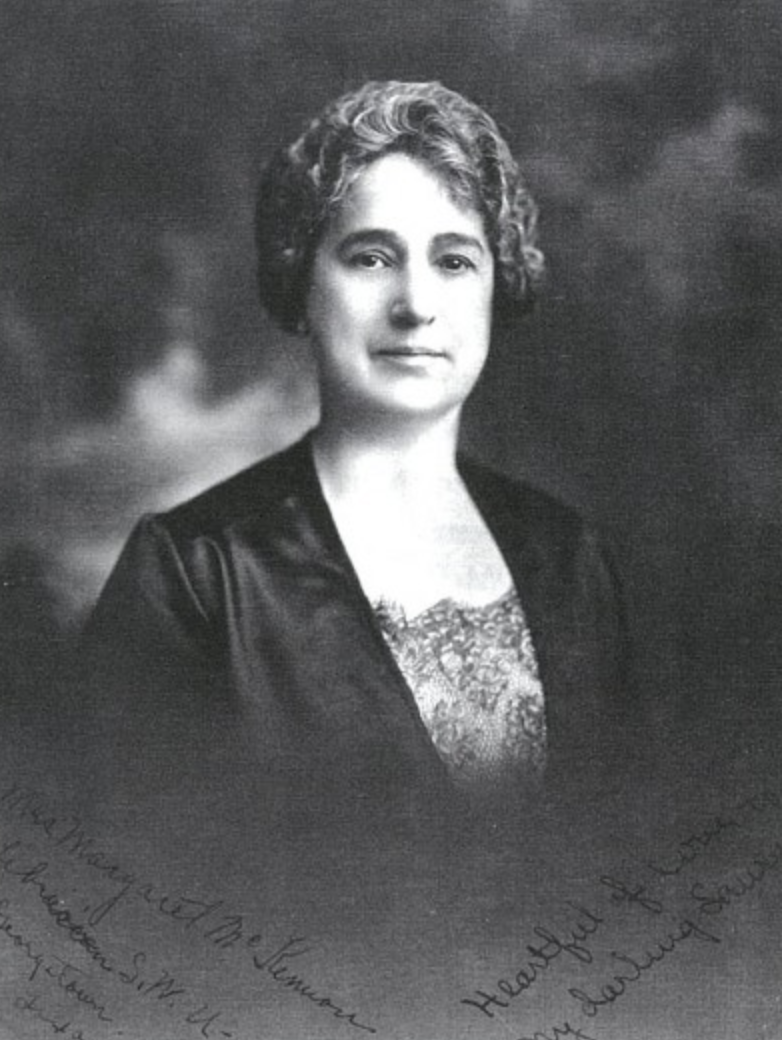

First fulltime librarian Margaret Mood McKennon; photo from the Southwestern University 1933 yearbook, The Sou’wester

You’ll want to thank Margaret Mood McKennon when you enjoy the SU library. Community members can come in, and check out materials with a TexShare card from their home library. Margaret was the first female to graduate SU with a full bachelor’s degree. After graduating from SU, she taught in several mission schools in Mexico from 1895 to 1900 before becoming SU’s first full-time head librarian at Southwestern in 1903.

When Margaret came on board as librarian, the library’s holdings consisted of a personal set of books owned by one professor. Margaret dug in, and by the end of her 35-year tenure, she had gathered a diverse collection of 50,000 volumes. She would serve 41 years at SU.

Inside the library, find more enriching experiences spearheaded by women. Townies can come to most all of the talks and events here, and they did show up for an extraordinary Writer’s Voice series brought here by Dean of Library Services Lynn Brody. Visit her alcove in the northeast corner of the first floor, and see amazing authors who came including Margaret Atwood, Mira Nair, and Amy Tan.

Lynn Brody and her alcove

Look over to the Debby Ellis Writing Center by the Brody alcove. Debby was a beloved English professor who died too young from a heart defect. SU named the student Writing Center after her. There, a plaque honors her; right above we see Debby’s short and valuable writing advice: “Get serious. Get done.”

Go upstairs to the cozy Women’s Studies Alcove on the third floor and browse their awesome women-centric books. Come back some day to settle in the comfy chairs and sample your finds.

bell hooks

Check out the photos of women such as bell hooks, who did a residency here; female-focused books; photos of luminaries who came here such as author, educator, and social critic bell hooks and feminist icon Gloria Steinem; and info about the Feminist Studies program here.

And of course, there’s homage to Jessie Daniel Ames, whose name is on a lecture series bringing fascinating speakers to campus. Just a few of the inspirational women who came as part of the lecture series from farmworker rights activist Delores Huerta—who is still a tireless activist at age 95—to feminist political theorist Wendy Brown.

Delores Huerta—still an activist at 95

Alma Thomas Fine Arts Center

Head over to the Alma Thomas Fine Arts Center. Since 1999, Alma’s center has housed the Sarofim School of Fine Arts, named for the Houston financier who has donated much to the school.

Take a look at the imposing original entrance to the Alma Thomas Fine Arts Center on the building’s west side. You’ll find a large portrait of Alma inside in an austere gown looking demure. But don’t take her for a languishing lady of leisure. Here’s her real story.

Alma Thomas in front of the action-packed Alma Thomas painting; photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Alma Thomas was born to a ranching family in Indian Territory in what became Oklahoma. She recalls that Lawton (in what would become Oklahoma) was just a collection of tents and saloons. She met rancher E. R. Thomas and married him in 1910. The two had two sons, and the family moved to a ranch near Midland.

Alma loved the ranching life. She often rode herd at roundups and she was as good as any cowpuncher. In 1923, her husband E. R. died from a fall off a windmill. She and the two teen sons kept the ranch going, and Alma and the boys moved to Austin, although they kept ownership of the ranch. All three of them went to UT, with Alma getting a degree in education and a master’s in economics. She was a principal and teacher for years.

Then Texas Tea—oil—was discovered on the ranch, and the family’s retained mineral rights proved to be a goldmine. A lifelong Methodist, Alma gave generously to Southwestern, funding what would be called the Alma Thomas Fine Arts Center with its Alma Thomas Theater.

The original entrance to Alma.

Alma also supported numerous arts organizations after moving to Austin, including the Zachary Scott Theater and the Austin Symphony.

And she spent that oil dough with her first love: Traveling. She went to 127 countries around the world by 1971, including doing the Taj Mahal with gal pals and a trip to the North Pole where she had to land in a helicopter. Even at home, she didn’t slow down—at 60, she broke a wild horse so that her grandchild would have a safer ride.

So many townies have joined students and faculty to enjoy theater and music at Alma’s theater!

Her friend, the author J. Frank Dobie, called her a “salt-of-the-earth woman,” and she was funny. She preferred not to have hoopla and visibility around her donations, and she had not been enthusiastic about sitting for her portrait to be hung in the Alma Thomas Theater. When her portrait fell to the floor during a particularly rousing piano concert, Alma chuckled and commented, “I now belong to the big class of fallen women.”

The Negro Fine Arts Program

Do you hear music? Alma’s building is where the music classes were and continue to be. And here is where an inspirational program started with the work of SU students and faculty.

Nettie Ruth hated racism.

In 1946, Southwestern University was not integrated. Many of the SU students wanted change, but it was slow to come. Nettie Ruth Brucks was a student who wanted change.

As a girl, her family had lived in Goldthwaite, a town outside of Austin with a sign on the edge of town that read something like, “If your skin is black, don’t let the sun set on you in our town.” Sundown cities were found in cities beyond the South—here’s one from a Connecticut city, part of a book written by sociologist James Louwen and website to help people learn more about sundown towns.

Elmina Bell

Nettie Ruth hated this sign and all the aweful segregation. She’d came to Southwestern to study music Christian Education and she belonged to the Student Christian Association (SCA). She and her music student friends Elmina Bell and Barbara Leon were angry when the SCA invited a Black man to speak, but then learned that the speaker couldn’t eat with them in the SU cafeteria. They went with him to eat potluck at the First Methodist Church down the street instead.

Barbara Leon

Nettie Ruth and other music students brainstormed a way to help Georgetown’s black children who were locked out of an education as good as the white kids. They came up with the idea of teaching music for free.

They’d been learning a teaching approach of teaching children in a group to play music, instead of one-on-one instruction. That method could help teach more students, they figured. They found strong leadership with their professors.

SU students worked with faculty to start and maintain SU’s Negro Fine Arts program to teach kids music. Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

SU music professor Iola Bowden was their number one advocate in getting their plans to reality. “She was the glue that got it going and kept it going for 20 years,” recalls Nettie Ruth. Iola (learn more about her here) had already been teaching Black youngsters privately. She helped move along what became the Negro Fine Arts School, reaching out to find teaching space for the program at the classrooms of the First Methodist Church a few blocks west on University. She went to the teachers in the segregated schools and asked them to find students who’d like to participate.

Music professor Iola Bowden and two students

Iola taught middle-school and high-school Black students alongside the students. Nettie Ruth, Elmina, and Barbara were the student teachers the first year, and other students joined them in following years of volunteer teaching. The children could also take classes in voice, art, and handcrafts.

The Black students had been walking all the way from Carver School west of downtown. SCA students paid for a bus driver to pick up Black children and bring them to the after-school classes and they helped buy more pianos in addition to the piano provided by the Carver PTA. By 1950, the SCA, together with Southwestern and the Methodist Church and the Kings Daughters women’s club, started providing scholarships for all students of the Fine Arts School who wanted to study music.

Nettie Ruth married Morris Bratton, another Southwestern student who became a minister. She worked with him doing church duties, and then began teaching in the public schools. She was the first Methodist minister’s wife in the Southwest Texas Conference to work outside the home. Many young women thanked her for giving them permission to work and embark on a career.

Nettie Ruth was awarded at Georgetown’s 2024 Juneteenth celebration.

Nettie Ruth has always been very involved in politics and nearly won a seat on the State Board of Education. She volunteered for many projects over the years to benefit people in central Texas. She continues to seek social justice on many fronts and inspire younger women.

Fine Arts program grads (L-R) Melza Smith, Birdie Shanklin, Paulette Taylor, and Alfred Fisher

And the Negro Fine Arts program created a wealth of benefits to hundreds of children. Over 200 students participated over the 20 years of the program. Many of the students went on to accomplish in the music sphere. Ernest Clark went to the Fine Arts program and went on to be the first African-American student to graduate from Southwestern in 1969. Clark became a music teacher who taught 36,000 students over his career.

Several other Negro Fine Arts graduates went on to teach as well, such as Carl Finley Henry, who taught music for 33 years in Dallas schools to thousands of young people.

Celebrating the naming of the Ernest Clark Hall (L-R): Sharon Clark; Dr. Terri Johnson, former SU Assistant Dean for Multicultural Affairs; Ernest Clark; Paulette Taylor, president of Georgetown Cultural Citizen Memorial Association and Negro Fine Arts grad

In the MOOD for feminism

Continue on to Mood-Bridwell. Built in 1908, it’s the oldest classroom building on campus. Like most universities and medical schools, Southwestern started out being male-only. Mood-Bridwell Hall was for many years the male dorm. Here are some enthusiastic Mood dudes.

Photo courtesy of Southwestern University Special Collections and Archives

Marta Cotera, lifelong activist

For much of Mood’s modern history, female professors and allies have been teaching feminist studies, mostly here and across campus. The interdisciplinary department began in 1989, but feminist and women’s history classes blossomed well before that. For many years, productions of Eve Ensler’s Vagina Monologues were held here in the atrium and at other campus spots.

Speakers with the Jessie Daniel Ames lecture series sometimes spoke here. The most recent speaker in the series is Marta Cotera, a lifelong activist for Chicana/o rights who’s still at it at 87!

Fondren-Jones Science Hall

Ella Fondren

Thanks, Ella! The newly renovated Fondren-Jones Science Hall has been around since 1954, when Ella Fondren wrote the check for the original Fondren Science Hall. Ella had it tough growing up in Corsicana: After her father died in 1895, she quit school to help care for her six siblings. She worked in her family's boardinghouse, where she met oil driller Walter Fondren.

Ella advised Walter on business moves as he went out acquiring more oilfields, while she took care of the three kids. Their holdings resulted in the founding of Humble Oil, which is now Exxon.

Ella also invested on her own early on in a venture that became Texaco. After Walter died, Ella financed the Fondren Science Hall. She went on to donate millions to hospitals, libraries, science institutions, and more.

If you want to finish your tour, hope you enjoyed it! If you’re ready for more, read on below for an extended tour as well as a SU-infused amble down University

Start your walk at the Red and Charline McCombs Campus Center. Circle around campus for a .5 mile stroll. For a look beyond, you might add a mile for a look at a few SU-linked spots off campus.

☛ Shout out to Charline McCombs at the Red and Charline McCombs Campus Center! Learn more about her above.

☛ Lois Craddock Perkins lives on in her beautiful chapel, but also in the women students whose college path was made possible by Lois Perkins Aid Fund for Young Women. The Chapel may not be open when you stop by, but look for special occasions to visit and see the lovely interior, such as the 105-year-old tradition of Candlelight Service to celebrate Advent and the Christmas season. When you do, thank Phoebe and Laura.

Phoebe Eleanor Jones Bishop’s husband was Dr. Charles McTyeire Bishop, the University’s president from 1910 to 1921, and Phoebe made Candlelight night happen, with the assistance of former Dean of Women Students Laura Kuykendall, who served Southwestern from 1914 to 1953.

At the 1915 service, a processional of 125 women filed into the Chapel amidst a congregation illuminated by candles singing Christmas hymns and accompanied by the Southwestern University Orchestra. Methodist pastors prayed, everyone sang holiday carols, the Christmas story was read, and everyone had a buffet dinner.

☛ If you’re facing the Chapel, go around the corner to your right to see the Madonna and Child sculpture. Eminent sculptor Charles Umlauf created this; check out the Umlauf Sculpture Garden in Austin.

Elizabeth Perkins Prothro

☛ Continue to your right around the promenade. Stop at the Charles and Elizabeth Prothro Center for Lifelong Learning. The building honors Charles Prothro and Elizabeth Perkins Prothro, the daughter of Lois Craddock and Joe Perkins. Elizabeth also focused her generosity on higher education here at SU, Southern Methodist University, and several other universities.

Charles and Elizabeth Prothro building

She bettered her hometown of Wichita Falls with scholarships at Midwestern State University and funding for the Wichita Falls Museum and Art Center and the Riverbend Nature Center. A published photographer, she supported the art of photography with the Elizabeth Perkins Prothro Photography Gallery at the Harry Ransom Center at UT, a photography book imprint, and more.

☛ Turn left after the Charles and Elizabeth Prothro building, and head up the sidewalk to the residence halls. Look to the hall on the left, Cody-Brown. Here’s about where the Ladies Annex and then the Laura Kuykendall Hall was located. Inspirational Dean of Women Students Laura Kuykendall lived and worked here and threw some AMAZING parties such as MayFest!

The May Festival in 1946, with Maypole, dancing, and general revelry

Imagine all the learning and fun and new horizons for SU women over the years!

☛ Look at the residence hall at the top of this cul-de-sac: It’s Ernest Clark Hall, named after the first Black SU graduate who went on to educate some 36,000 students in his career.

☛ Turn around and head back down the sidewalk toward the Alma Thomas Fine Arts Center. If the building is open (campus buildings are at certain times only accessible to students), walk in. If you keep walking after traversing the long hall, look to your left for the large portrait of Alma Thomas close to the front windows near the Sarofim School of Fine Arts entrance. Hopefully she and her portrait won’t ever again be one of Those Fallen Women!

Genevieve Britt Caldwell

☛ Look around the lobby and see the plaques honoring donors, including several women. Here’s a bit about the life of just one: Genevieve Britt Caldwell, SU class of 1942. She grew up in the windswept Panhandle and attended a one-room schoolhouse. She followed a family tradition of heading to SU, and graduated with honors in 1942.

Genevieve looked for a job to support the war effort, and worked at the Pantex Ordnance plant. She married torpedo bomber pilot “Red” Caldwell, who had a saddle-making business. While she raised two children, she gave her energies to improve many things Amarillo, including music, art, the history museum, support for people with cancer, and the Boy and Girl Scouts. She was a tireless SU recruiter, sending over 135 students to study here. Genevieve died at 98 in 2003.

Women’s Studies Alcove

☛When you come out the west side of Alma Thomas, head left down the sidewalk to see the original entrance with Alma’s name. Head west past the fountain and turn right to enter the Smith Library’s main door.

Go upstairs to the cozy Women’s Studies Alcove and browse their awesome women-centric books.

☛ Go left after leaving the main door of the library, and then left again towards the beautiful new Fondren-Jones Science Hall. A tip of the hat to Ella Fondren, who funded the original Fondren Science Hall in 1954. Ella had married Walter William Fondren, who was one of the founders of Humble Oil company, which then became Exxon.

Ella Fondren: Mom and moneymaker

As William Burwell Jones writes in the fascinating SU history, To Survive and Excel: The Story of Southwestern University, Ella worked with Walter, advising him on oil field picks and investments as she simultaneously raised a family. Ella also invested on her own early on in a venture that became Texaco. After Walter died, Ella wrote her own check for the Fondren Science Hall.

☛ Turn the opposite direction from Fondren-Jones to face the majestic old Mood-Bridwell Building. Built in 1908, Mood was a man-palace for many years, but was at other times an all-women’s residence and the residence for many of the Naval trainees during the war years. For much of its more recent years, Mood was and is a mecca for Feminist Studies classes and speakers.

☛ Turn around again and head toward University Avenue on the sidewalk between Fondren-Jones and SU’s oldest building, the Cullen administration building.

At the end of the sidewalk, look left to see a low cement stand with a smooth top. This is where for decades this marker commemorated Georgetown’s Woman’s Club. Sometimes the women met on campus.

See more about the huge impact of our women’s clubs over the years here.

☛ Come back out toward the SU clock and circle to the left of the Welcome Center and stop at the Physical Plant’s giant air conditioner. Isn’t the SU campus gorgeous? But that beauty is brought to you by many dedicated employees. Like a lot of “women’s work,” it’s invisible but crucial to do the work that keeps everything flowing. Let the AC unit inspire us to give deep thanks to all the employees who keep the air conditioning flowing during the summer and everything running spit-spot. Bow to the housekeepers who keep all the buildings clean and inviting, and all the kitchen folks who keep everyone fed.

Martha, second from left with honoree Esther Messick Weir

Here’s one SU housekeeper, Martha Diaz Hurtado, who worked here for 20 years. She was so well-loved that SU started the Martha Diaz Hurtado College-Town Award in 2006. Here’s Martha with recipient Esther Messick Weir. Esther taught at SU many years after arriving here in 1938 at age 22. She then went on to be a leader in the largely female-led effort to revive the Georgetown Square after the businesses had become shabby after business traffic moved to the new I-35 area.

Esther got the Hurtado award along with her daughter Laura, who also did much to revive the Square. If you’ve admired the onion-domed building on the northeast corner of the Square that currently houses the Italian restaurant Juliet, Laura’s the one who rescued it from a sad shape.

And artist Norma Clark, a 1997 SU grad, also was given the Hurtado award. Norma created a beautiful abstract mural for the Shotgun House Black History Museum in downtown Georgetown. DO go look at her beautiful abstract mural there at 9th and West streets.

Check out my resource guide to all the Black Georgetowners in Norma’s painting who did so much for the community.

☛ Continue on Maple Street to Kourova Milkbar, in the old Fieldhouse that’s now home for the campus police. Kourova was a space to be comfortable no matter who you were.

Groups could hold events here—everyone from Feminist Voices to the environmental student group to Black History poetry night and more. In a campus where Greek weekend parties are the big social events, folks could find a welcome spot at Korouva, plus cheap coffee and other refreshments.

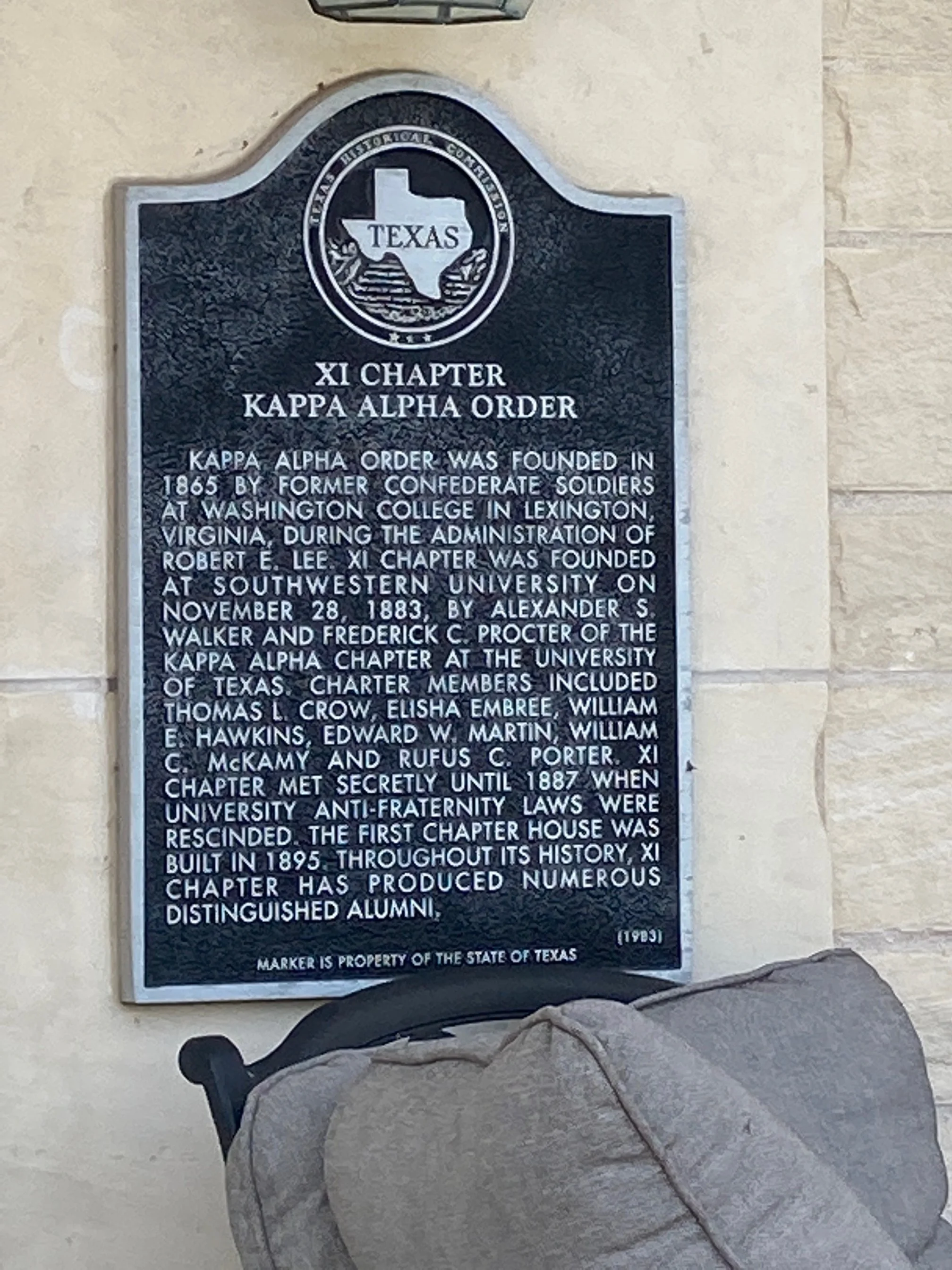

☛ Take a right at MacKenzie Drive for a look at frat house row. The Kappa Alpha house is on the right. As the marker on its porch notes, KA was founded in 1865 by former Confederate soldiers when Dixie was headed by Robert E. Lee.

Over the years, the chapter here and others among its 120-some chapters have been criticized for reveling in its Confederate roots, hosting antebellum formals and reciting chants lamenting the Union victory in the Civil War. More recently, three Kappa Alphas from the University of Mississippi posed with guns at a memorial for Emmett Till, the Black teenager whose horrific lynching made him a namesake of the federal anti-lynching bill passed in 2022.

In recent years, the SU chapter has drawn national attention for refuting their Confederate past. SU members demanded that the fraternity nationwide drop its association with Lee and investigate the racial harms they say Kappa Alphas have inflicted. The action was initiated in 2019 by Noah Clark, the first Black student graduating as an active KA member. Kappa Alpha Order’s national organization then suspended the SU chapter for a year, as well as other chapters calling for similar actions.

Margarett

☛ Cross McKenzie Drive to see the Kappa Sigma House to the right and the Pi Kappa Alpha House on the left. Pass between these frat houses to approach the Herman Brown Residence House, and give a salute to Herman’s spirited and influential spouse, Margarett (see above for more on this independent and accomplished woman).

Take the path to the next building that leads us to another notable SU woman, Mary Moody Northen. Feeling like buying some eggs?

Moody-Shearn Residence Hall

Mary was born into a wealthy Galveston family in 1892, and as such made her debut into society and was tutored at home. However, she was also a bustling businessgirl early on with her Great American Chicken Company, where she sold eggs and chickens to family and friends. As a married woman with no chldren, she’d meet with her dad nightly to discuss the doings of the family enterprises. William L. Moody, Jr., was grooming Mary, not his sons, to take over the family empire.

When her dad died, Mary became president of their many holdings, including a national insurance company, bank, and a newspaper publishing company. She chaired or would chair some 50 organizations, including the family foundation, their cotton company, hotel chair with nearly 40 hotels, and a ranch company with holdings in three states.

Mary Moody Northen

Mary established the Mary Moody Northen Endowment in 1964. She funded the construction of the Moody-Shearn Hall, adding her grandfather’s name in its naming. John Shearn graduated in 1845 from Rutersville College, a college that merged into Southwestern when it began in 1873.

Mary also used her Foundation to build the Texas A & M Maritime Academy and preserve historical properties such as the 1877 ship Elissa, turn an abandoned depot into a railroad museum, and turn her mansion into a museum. Tour the Moody Mansion on Galveston Island to see the roots of this ambitious woman!

☛ Keep looking north as you leave Mary’s dorm. See that modest building on the corner with the Greek letters on the wall? That’s the Sharon Lord Caskey Center, funded by businesswoman Sharon (her parents, Grogan and Betty Fowler Lord, are the namesakes of the student housing beyond Sharon’s center.)

This building is where SU’s sororities are allowed to meet in separate chapter rooms. In contrast to the voluminous houses afforded the fraternities, SU sorority sisters have had to fight for a place to meet. Sorority members who are salty over their diminished space are told that the lack of sorority houses on campus springs from a Williamson County statute that way back when limited the number of women living in the same house. The fear was that such houses would become places of prostitution.

Various SU administrators also feared parent wrath when delicate females were in their own houses and could more easily flout the heavy-handed oversight of said females. Plus, by the time the fraternities took up their space, women were told that there wasn’t space to build sorority houses.

Alpha Delta: First SU sorority

Nevertheless, the women persisted, going back to the start of the 1900s. Women students including Jessie Daniel (who’d later lead the suffrage battle in Williamson County and found an anti-lynching organization in Atlanta) asked then president Robert Hyer to start a sorority; they were refused. Two years later in 1903, three sororities were allowed, including Alpha Delta.

Sororities get a meeting room here.

Over the years, sororities met at the Women’s Building, later called Laura Kuydendall Hall. Now they meet here for meetings at their Center room, and arrange to hold their parties and formals elsewhere. Many students still believe that Greek-minded women should have their own houses, but as this 2022 student newspaper report notes, it may never happen.

If you want to stop your walk now, head back to wherever you picked as your tour beginning.

SU in the Community

Want to see some nearby sites where SU actually began and where important racial justice work was done? Then take a stroll down University Avenue. Start at the Cullen administration building at University and Maple. Before you head west on University, look across the street to the empty lot that’s slated to be bustling soon with a student pub. This was once the site of the Pirate Tavern.

Here at the Pirate Tavern, students flocked to sip sodas, mail letters, and sashay around in sock hop socials. The joint opened in 1930, and the Tavern was quite the draw. In 1943, SU bought the Tavern and hosted a soda fountain and post office until the last soda was sipped in 1957. It was used for various SU program offices, and then torn down.

☛ Head west (toward downtown) on University (wonder why it was named that?) to see where SU started. Stop when you get to College Street. Guess why it’s called College Street. Yep, because that’s where Southwestern University—called Georgetown College initially—started.

Look at the grand space between College and Ash and going way back four streets to 8th street. Check out the Southwestern marker in front of Hammerlun.

Ann Morris Giddings

Notice the mention of Giddings Hall. Give a thanks to Ann Morris Giddings, who not only funded the boys’ dorm which was first called “Helping Hall” but also funded other cottages for female and male students of lesser means. Ann, married to Brenham baron Jabez Demming Giddings, funded the Girl’s Cooperative Home and several other cottages for students who got free lodging and board at cost so they could afford to go to SU. In gratitude, the students insisted that the dining hall adjacent to Helping Hall be named Giddings Hall.

☛ Go kitty-corner from Hammerlun to the magnificent First United Methodist Church so you can read the historical marker on the building about the Negro Fine Arts program housed here for 20 years. Find details on that wonderful project above!

☛ Look south down Ash Street and imagine that you lived here over a century ago and desperately needed a hospital. You’d be so close to the King’s Daughters Sanitarium, built with the leadership of Georgetown women at 15th and Ash. The Sanitarium was up and running just in time to treat our few victims of the Spanish Flu epidemic and save citizens from an epidemic outbreak here!

☛ Head up Ash and circle right on 8th St. to continue back to SU. Follow 8th St. as it curves left on Holly to meet 9th. Turn right and go to the train tracks. Picture what once was: the Katy railroad station—very popular with SU students to hop on and head off to Austin or another destination!

SU students could hop on the train right by campus and head to Austin and parts beyond.

☛ Cross the tracks and go right on Maple to head back to your beginning.